As an American of Japanese descent, I am an expert on all things Japanese.

Admittedly, I’ve spent little time in Japan, I can’t read the language, and I’ve never studied anything relating to – or rhyming with – Japan. Nonetheless, I satisfy the two prerequisites necessary to be recognized as an authority on the Japanese: (1) I have a Japanese name and (2) I eat rice. This explains why strangers – who don’t know that I speak perfect Asian – nonetheless consider me the spokesperson for Japan and ask questions such as: “What, exactly, is wasabi?,” “Why did you rape Nanking?,” and “Are you a sumo wrestler?”

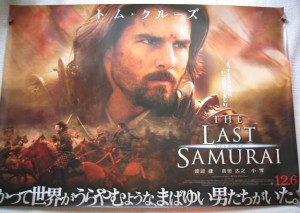

More recently, I’ve been carpet-bombed with questions about the veracity of events depicted in the epic film The Last Samurai . It seems everyone trusts my answers to complicated questions about the Meiji era of Japanese history, simply because I can pronounce “tamagotchi.”

So by request, let me take this opportunity to explain the answer to the burning question: “Was Tom Cruise really the last Samurai?”

The answer is a resounding, unconditional yes! The proof lies in the film itself, which is, actually, a documentary of the Samurai revolts.

A brief overview: Tom Cruise is an alcoholic American civil war general requested by the effeminate Emperor of Japan to train their first modern, conscript army to fight any rebellions. Shortly after the Emperor shows Tom Cruise the money, ancient warriors known as the Samurai easily defeat Cruise in battle. Not only do they stop him from completing his mission, they had him at hello.

However, instead of beheading Tom Cruise, the tribe of Samurai – who are bitterly opposed to opening Japan up to Western influences – choose to keep him alive because, naturally, they are open to his Western influences. In a few months of captivity, Tom Cruise masters the way of the Samurai and the Japanese language. (The latter of which turns out to be unnecessary since the leader of the English-hating Samurai speaks perfect English, evidenced by his careful enunciation of fortune cookie messages.) The distrustful Samurai, naturally, grow to trust Tom Cruise, especially after watching him rock climb Mount Fuji with his bare hands while receiving secret messages through his explosive sunglasses. Master Cruise and the Samurai join forces to fight the Japanese army, as well as a few ninjas.

The film beautifully captures the crucial turning point in Japanese history where Cruise manages to dodge 39,495,271 rounds of bullets, while all the Japanese Samurai around him fold like crumpled origami. What explains Tom Cruise’s seeming immortality? The answer is simple. He is a vampire. Unfortunately, he did not grant immortality to any of the Samurai by biting them because, apparently, he doesn’t like Japanese food.

While Cruise neglected to create a little vampire Samurai girl, he did manage to find romance in Japan, as documented in the movie. A Japanese woman named Taka (which means “Fallopian tubes” in Japanese) falls in love with Tom Cruise, who, by the way, had just finished killing Taka’s husband in battle. Why would a woman choose to do the nasty with her late husband’s murderer and then dress him up in her dead lover’s battle outfit? She is either enraptured by Cruise’s ability to seduce and destroy, or, quite simply, she respects the c*ck. Regardless, her behavior conforms to the new traditional Bushido code of loyalty: “Thou Shalt Love The Man Who Decapitates Thy Husband.” In terms of important cultural developments, this commandment is second only to Top Ramen’s invention of “Oriental Flavor.”

While The Last Samurai bravely captures this one era, it fails, far and away, to elucidate other important ways in which Tom Cruise has impacted Japanese history.

For example, little is known about how Tom Cruise was also an ace Navy pilot who, during World War II, trained Japanese kamikaze pilots in the ways of aerial dog fights. He earned the nickname “Maverick” after teaching them to fly right into the danger zone and introducing karaoke to the Japanese with his rendition of “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling.” Although Emperor Hirohito initially believed that Tom’s ego was writing checks his body couldn’t cash, the Emperor sent a telegram to Maverick-san on the morning of December 7, 1941 that read “Banzai!” (roughly translated: “You can be my wingman, anytime.”) Unfortunately, Tom Cruise never received this message because it was intercepted at Pearl Harbor by Ben Affleck.

While Tom Cruise’s impact on the development of Japanese history is too expansive to cover in one essay, there are many other documentaries that capture his influence. For the rise of the Japanese fuel-efficient automotive industry in the 1980s, I recommend the film Days of Thunder . To witness how Tom Cruise convinced the Japanese government to accept Commodore Matthew Perry’s demand to open ports for trade during the Edo period, I recommend Risky Business . For a depiction of how Tom Cruise convinced an elf, a fairy, and a pack of gnomes and trolls to fight against the Lord of Darkness in the Sino-Japanese War, I recommend either Legend or Eyes Wide Shut .

Well, that’s it for now.

Next week: did Kevin Costner actually join the Sioux tribe and defeat Custer at his last stand? We’ll talk to my friend Alex who is an expert on Native American history since he once built a teepee as a Boy Scout.